Alfred Adler Personality Theory Pdf

Personality TheoryCreated July 7, 2017 byAlfred Adler was an early member and president of theVienna Psychoanalytic Society, but he never considered himself a follower ofSigmund Freud. He strongly disagreedwith Freud’s emphasis on sexual desire in the development of personality,focusing instead on children’s striving for superiority and the importance ofsocial relationships. He began toaddress the psychology of women as a cultural phenomenon, as opposed to Freud’sview that women are fundamentally incapable of developing a complete andhealthy personality. Adler alsoaddressed issues of education, an individual’s unique perspective on the world,and family therapy. Adler provided aperspective in which the striving of individuals to improve themselves is anessential characteristic of personality development. Most importantly, he believed that personalimprovement and success are best achieved in cooperation with others, and thatculture is an important factor in determining how that can be accomplished.Ithas been suggested that Adler may have had an even greater influence on theoverall development of psychiatry and psychology than Freud himself, and thattheorists such as Sullivan, as well as Karen Horney and Erich Fromm, should berecognized as neo-Adlerians, not neo-Freudians (Ellis, 1973; Kaufmann, 1992;Mosak, 1995; Watts, 1999). Indeed, areviewer of one of Karen Horney’s books once wrote that Horney had just writtena new book by Adler (see Mosak, 1995).Albert Ellis suggested that Adler set the stage for thecognitive/behavioral psychotherapies that are so popular today (Ellis,1973).

Late in life, Adler encouragedthe wife of a good friend to write his biography, and he gave Phyllis Bottome,who was herself a friend of Adler, a great deal of assistance (Bottome,1957). He wanted to be understood. Perhaps, however, she came to understand himtoo well:Adler was at once the easiest of men to know, and themost difficult; the frankest and the most subtle; the most conciliatory - andthe most ruthless. As a colleague he wasa model of generosity, accuracy and wholehearted integrity, but woe betide thatcolleague who dared to presume upon his generosity; or who was himself guiltyof inaccuracy; or who failed in common honesty!Adler never again worked with a person whom hedistrusted; except when that person was a patient. 13; Bottome, 1957)Adler also had the ability to make an impression onpeople who did not know him.

WhenRaymond Corsini, a well-known psychologist in his own right, was 21 years old,he was invited by a friend to hear Adler speak at the City College of NewYork. During the question period thatfollowed the lecture, an angry woman called Adler stupid, and berated one ofthe observations he had discussed. Theyoung Corsini shared Adler’s perspective, and Corsini looked forward to hearingAdler’s “crushing reply.” However,something quite different occurred:He seemed interested in the question, waited a moment,then in the most natural and careful manner, completely unruffled by herevident antagonism, spoke to her very simplyHe seemed so calm, so reasonable, so precise, and sokind, I knew we were in the presence of a great man, a humble and kind person,one who repaid hostility with friendship. 86; Corsini cited in Manaster,et al., 1977)Harry Stack Sullivan extended Adler’s focus on theindividual and social interest, believing that each of us can be understoodonly within the context of our interpersonal relationships. Like Freud, Sullivan focused intently ondevelopmental stages, though he recognized seven of them, and believed that theprimary purpose of development was to form better interpersonalrelationships.

In regard to his interestin relationships he can be closely associated with Adler, who believed thatsocial interest, and its resulting social interaction, was the best way for anindividual to overcome either real inferiority (such as in the case of ahelpless newborn) or feelings of inferiority that might develop as part ofone’s personality. Unlike Freud andAdler, however, Sullivan was born in America.Thus, he should be considered one of the most important figures inAmerican psychology, particularly within the field of psychodynamic theory. Brief Biography of Alfred AdlerAlfred Adler was born on February 7, 1870, on theoutskirts of Vienna. The second of sixchildren, the family was fairly typical of the middle-class. His father was a corn-merchant, and did wellin his business.

While Adler while stillquite young the family moved out into the country, where they kept cows,horses, chickens, goats, rabbits, and they had a very large garden. Adler was particularly fond of flowers whenhe was a toddler, and the move out of Vienna had the consequence of protecting himfrom his bad habit of stealing flowers from the garden of the Palace of Schonbrunn,which belonged to the Kaiser!

Despitethe seemingly idyllic setting, and the family’s financial comfort, Adler didnot have a happy childhood. The two mainreasons for this were his sibling rivalry with his older brother and theunfortunate fact that he seemed to be surrounded by illness and death (Bottome,1957; Manaster, et al., 1977; Sperber, 1974).His older brother seemed to be an ideal child, and Adlerfelt he could never match his brother’s accomplishments. Even late in life, Adler told Phyllis Bottomewith a sigh “My eldest brotherhe was always ahead of mehe is still ahead of me!” (pg. 27; Bottome,1957). As for his younger brothers,however, one felt the same sort of jealousy of Adler himself, whereas theyoungest brother adored Adler. As forthe illness and death, he suffered from rickets (a vitamin D deficiency) andspasms of his vocal cords, both of which made physical activity very difficultduring his early childhood years. He wasoften forced to sit on a bench while watching his older brother run andjump.

As he recovered, he joined hisbrother and the other local children in playing in a large field. Despite the fact that there were very fewvehicles at the time, and those that were there moved very slowly, Adler wasrun over twice! Fortunately, he was notinjured seriously.

One of his youngerbrothers, however, had died suddenly when Adler was 4, an event that deeplyaffected him. And when Adler was 5, hecame down with a serious case of pneumonia.After he had been examined by the doctor, Adler heard the doctor tellhis father that there was no point in caring for Adler any more, as there wasno hope for his survival. Adler wasstricken with terror, and when he recovered he resolved to become a doctor sothat he might have a better defense against death (Bottome, 1957; Manaster, etal., 1977; Sperber, 1974).On the lighter side, most of the family was musicallygifted. One of his brothers played andtaught the violin, and one of his sisters was an excellent pianist.

Despite the throat problems Adler had inearly childhood, he developed a beautiful tenor voice. He was often encouraged to set aside hisinterest in science and pursue a career as an opera singer. Adler’s parents encouraged the musicalinterests of their children, and took advantage of the marvelous musicalculture available in Vienna at the time.Adler attended every opera and play that was running, and even by theage of 4 years old could sing entire operettas (Bottome, 1957; Manaster, etal., 1977; Sperber, 1974).Although Adler spent a great deal of time reading, he wasnot a particularly good student. Hisworst subject was math, until he finally had a breakthrough one day. When the instructor and the best student inclass failed to solve a problem, Adler raised his hand. Everyone in the room, including theinstructor, laughed out loud at him.However, he was able to solve the problem. After that, he did quite well in math, andoverall he did well enough to enter the University of Vienna.

He studied medicine, as he had planned sincebeing a young child, and graduated in 1895.Almost nothing is known of his time spent at the University ofVienna. Afterward, he briefly practicedophthalmology, but then switched to general practice, a field in which he wasvery popular amongst his patients. Healso became active in socialist politics, where he met his future wife: Raissa Timofeyewna Epstein (Bottome, 1957;Manaster, et al., 1977; Sperber, 1974).Raissa and Alfred Adler had three daughters and one sonbetween the years 1898 and 1909. Thefamily lived rather simply, but they always had enough to meet theirneeds.

Their daughter Alexandra and sonKurt both became psychiatrists.Alexandra Adler described her relationship with her father as close andpositive, and she considered it a privilege to follow in his footsteps, whereasKurt Adler said that everyone in the family felt respected as an individual andthat no one had to search for their identity (see Manaster, et al., 1977).In his general practice, Adler began to see psychiatricpatients. The first was a distant cousinwho complained of headaches.

Adlersuggested that no one ever has only aheadache, and asked if her marriage was happy.She was deeply offended, and left in a huff, but 2 months later shefiled for divorce. As he saw morepsychiatric patients, Adler treated each case as unique, and followed whatevertherapy seemed most appropriate for the particular patient. This was the beginning, of course, ofIndividual Psychology. Adler was sopopular in this regard that his biographer had the following experience herselfwhen leaving a message for Adler:‘Are you sure’, she asked the clerkat the desk, ‘that Professor Adler will get this message directly he comes in?’sic ‘Adler?’ the clerk replied. ‘Ifit’s for him you needn’t worry. Healways gets all his messages.

You canhardly keep the bell-boys or the porter out of his room. They’ll take any excuse to talk to him, and as far as that goes, I’m not muchbetter myself!’ (pg. 54; Bottome, 1957)In 1900, Sigmund Freud gave a lecture to the ViennaMedical Association on his recently published book The Interpretation of Dreams (Freud, 1900/1995).

The audience was openly hostile, and Freudwas ridiculed. Adler was appalled, andhe said so publicly, writing to a medical journal that Freud’s theories shouldbe given the consideration they deserved.Freud was deeply flattered, he sent his thanks to Adler, and the two menmet. In 1902, Adler was one of fourdoctors asked to meet weekly at Freud’s home to discuss work, philosophies, andthe problem of neurosis. These meetingevolved into the Psychoanalytic Society.Adler and Freud maintained their cooperative relationship for eightyears, and in 1910 Adler became the president of the InternationalPsychoanalytic Association and co-editor of the newly established Zentrallblatt fur Psychoanalyse (withFreud as Editor-in-chief). During thepreceding 8 years, however, the differences between Freud and Adler had becomeincreasingly apparent. By 1911 he hadresigned from the both the association and the journal’s editorial board.

Although Freud had threatened to resign fromthe journal if Adler’s name was not removed, leading to Adler’s own decision toresign from the journal, Freud urged Adler to reconsider leaving the discussiongroup. He invited Adler to dinner to discussa resolution, but none was to be found.Adler is said to have asked Freud:“Why should I always do my work under your shadow?” (pg. 76; Bottome,1957).

Alfred Adler Personality Theory Ppt

The Psychoanalytic Societydebated whether or not Adler’s views were acceptable amongst the members of thesociety. The no votes counted fourteen,and the yes votes counted nine. Freud’ssupporters had won a small majority, and the nine other members left to joinAdler in forming a new society, which in 1912 became the Society for IndividualPsychology (Bottome, 1957; Manaster, et al., 1977; Sperber, 1974).During the years in which Adler was still active in thePsychoanalytic Society he had begun his studies on organ inferiority and theinferiority complex, and after the split with Freud he focused his career onpsychiatry (giving up his general medical practice). During World War I he served in the Army as aphysician, and he continued his observations on psychiatric conditions as hehelped injured servicemen.

Following thewar the Austrian Republic began to emphasize education and school reform. Adler established his first child guidancecenter in 1922, and by the late 1920s there were thirty-two clinics in Viennaalone (as well as some in Germany). Theclinics were intended to help train teachers to work with special needs children,but Adler felt it was important to help the children themselves as well. In 1930, Adler brought together a number ofhis colleagues, including his daughter Alexandra, and published Guiding the Child: On the Principles ofIndividual Psychology. This volumecontains twenty-one chapters on the work being conducted in the Vienna childguidance clinics (including one chapter by Adler, and two by his daughter;Adler, 1930a).

In addition, Adler taughtat an adult education center and at a teacher training college. Adler continued to be so popular that after along day of work he would settle in at the Cafe Siller and carry on friendlyconversations until late at night.In 1926, Adler made his first visit to America. Becoming a regular visitor, he lectured atHarvard and Brown Universities, in Chicago, Cincinnati, Milwaukee, and severalschools in California. In 1929, he wasappointed a visiting professor at Columbia University, and in 1932 he wasappointed as the first chair of Medical Psychology in the United States, atLong Island Medical College.

All of hischild guidance clinics were closed when the fascists overthrew the AustrianRepublic in 1934, and Alfred and Raissa Adler made New York their officialhome. In the spring of 1937 he began atour of Europe, giving lectures and holding meetings. As he traveled to Aberdeen, Scotland on May28 th, he collapsed from a heart attack and died before he reachedthe hospital.One of the enduring questions about Adler’s career wasthe nature of his relationship with Freud.As mentioned above, it was the very popular Adler who defended Freud’searly theories, and helped Freud to gain recognition in psychiatry (rememberthat Freud was well known as an anatomist and neurophysiologist). And yet, it is often suggested that Adler wasa student or disciple of Freud.According to Abraham Maslow, Adler was deeply offended by thesesuggestions:I asked some question that impliedhis disciplineship under Freud. Hebecame very angry and flushed, and talked so loudly that other people’sattention was attracted.

He said that thiswas a lie and a swindle for which he blamed Freud entirely. He said that he had never been a student ofFreud, or a disciple, or a followerFreud, according to Adler, spread the versionof the break which has since been accepted by all - namely, that Adler had beena disciple of Freud and then had broken away from him. It was this that made Adler bitterI neverheard him express personal opinions of Freud at any other time. This outburst must, therefore, be consideredunusual. 93; Maslow cited in Manaster, et al., 1977; see also Kaufmann,1992)PlacingAdler in Context: Perhaps the MostInfluential Person in theHistory of Psychology and PsychotherapyTo suggest that anyone may have beenmore influential than Freud, let alone a contemporary of Freud, is difficultto say.

And yet, if we look honestlyat the accomplishments of Alfred Adler, and the breadth of his areas ofinterest, we will see that the case can be made. When Freud first proposed his psychodynamictheory, with its emphasis on infantile sexuality, Freud was often mocked, orsimply ignored.

It was the popular Dr.Adler’s defense of Freud, and Adler’s favorable review of the interestingnature of Freud’s theories, that helped Freud find an interestedaudience. As supportive as Adler was,he had his own theories from the very beginning of their association, andAdler’s Individual Psychology has a certain logical appeal, without thecorresponding controversy generated by Freud.Infants are inferior, and we all try togain control over our environments.Thus, the basic inferiority/striving for superiority concept seemsself-evident. Likewise, theinferiority complex is one of the most widely recognized and intuitivelyunderstood concepts in the history of psychology. Suggesting that each person adopts a styleof life that helps them to pursue their goals also again makes perfect sense,and the suggestion that we have within us a creative power to form our styleof life is a decidedly hopeful perspective on the human condition.Adler’s influence within thepsychodynamic field has been widely recognized, if not adequatelyadvertised.

When he split with Freud,nearly half of the psychoanalytic society left with him. His emphasis on social interactions andculture provided a framework within which theorists such as Karen Horney andErich Fromm flourished. Adler’semphasis on child guidance, and including school teachers as being just asimportant as parents, must have had an important influence on Anna Freud(though she would never have admitted it).Within the child guidance centers, Adler was one of the first (if notthe first) to utilize family therapy and group psychotherapy, as well asschool psychology. It was within suchan environment, influenced also by Maria Montessori, that Erik Eriksonevolved into the analyst and theorist he became.Adler’s influence also extended wellbeyond the psychodynamic realm.

Hisscheme of apperception set the stage for the cognitive psychology andtherapies that are so popular (and effective) today. He is recognized by many as the founder ofhumanistic psychology, though it was Rogers, Maslow, and the existentialistsViktor Frankl (Frankl worked closely with Adler for a time) and Rollo May whoclearly split from psychodynamic theory into new schools of psychology.Given this extraordinary influence, itis surprising that Adler is not widely recognized as belonging amongst thegreatest theorists and clinical innovators in the history of psychology andpsychiatry. The honor is certainlywell deserved. Adler's Individual PsychologyAdler developed the concept of Individual Psychology out of his observation that psychologistswere beginning to ignore what he called the unity of the individual:A survey of the views and theories of mostpsychologists indicates a peculiar limitation both in the nature of their fieldof investigation and in their methods of inquiry. They act as if experience and knowledge ofmankind were, with conscious intent, to be excluded from our investigations andall value and importance denied to artistic and creative vision as well as tointuition itself.

Alfred Adler Personality Theory Pdf Online

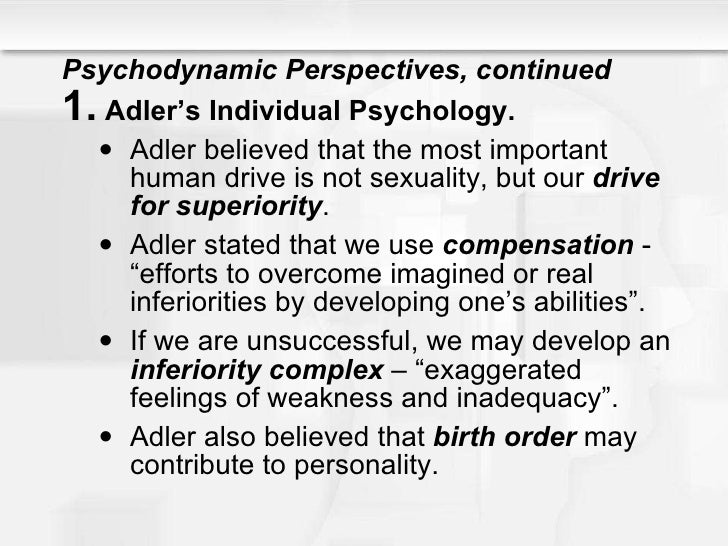

1; Adler, 1914/1963)To summarize IndividualPsychology briefly, children begin life with feelings of inferiority toward their parents, as well as toward the wholeworld. The child’s life becomes anongoing effort to overcome this inferiority, and the child is continuouslyrestless. As the child seeks superiority it creatively forms goals,even if the ultimate goal is a fictional representation of achievingsuperiority. Indeed, Adler believed thatit is impossible to think, feel, will, or act without the perception of somegoal, and that every psychological phenomenon can only be understood if it isregarded as preparation for some goal.Thus, the person’s entire life becomes centered on a given plan forattaining the final goal (whatever that may be). Such a perspective must be uniquelyindividual, since each person’s particular childhood feelings of inferiority,creative style of life, and ultimate goals would be unique to their ownexperiences (Adler, 1914/1963).The suggestion that seeking to overcome one’sinferiorities is the driving force underlying personality development is, ofcourse, a significant departure from Freud’s suggestion that developmentrevolves around seeking psychosexual gratification.

Another important difference is that Adler didnot distinguish between the conscious and unconscious minds as Freud had:The use of the terms “consciousness” and“unconsciousness” to designate distinctive factors is incorrect in the practiceof Individual Psychology. Consciousnessand unconsciousness move together in the same direction and are notcontradictions, as is so often believed.What is more, there is no definite line of demarcation betweenthem. It is merely a question ofdiscovering the purpose of their joint movement. 56; Adler, 1929a) Inferiority and CompensationIn 1907, Adler published his classic Study of Organ Inferiority and Its Psychical Compensation, whichwas translated into English 10 years later (Adler, 1917). This was primarily a medical article on theconsequences of organ inferiority,in which Adler looked at how the nervous system helped the body to adapt tophysical infirmities that resulted from, literally, inferior organdevelopment. For example, it is oftensuggested that people who are blind develop better hearing.

However, social psychologists havedemonstrated that the social environment can profoundly affect our sensitivityto external stimuli. The reason for thisis probably just what Adler described as the primary means through which thebrain can compensate for any deficiency:by bringing attention to the processes necessary for compensation. Thus, if a person has difficulty seeing, theypay more careful attention to hearing, as well as to the other senses.

However, this is not a perfect system, and itcan also lead to over-compensation. As aresult, a wide variety of physical symptoms can result from the psyche’sefforts (including unconscious efforts) to compensate for some problem. As noted by Freud, hysterical symptoms aretypically manifested as physical problems.According to Adler, underlying these physical symptoms, even when theyare caused solely by the psyche, there must be some organ inferiority withinthe body (Adler, 1917).Adler did not limit his theory of organ inferiority tomedical problems or neurotic symptoms, but rather, he expanded the theory toincorporate all aspects of life. Compensation refers to the typicalmanner in which a person seeks to overcome challenges. For example, if one breaks their arm, theylearn to function with a cast, or if one loses their eyesight, they learn touse a cane or work with a seeing-eye dog (Dreikurs, 1950; Mosak & Maniacci,1999). If we examine compensation in amore psychosocial realm, examples might include a college student who cannot finda suitable boyfriend or girlfriend so they focus on becoming a straight Astudent, a student who does not do well academically focuses their efforts onbecoming a star athlete, or an only child who wished to have brothers andsisters has many children of their own (Lundin, 1989).

In such instances, compensation leads tobalance in one’s life. A weakness, or atleast a perceived weakness, is compensated for in other ways (Manaster &Corsini, 1982). Overcompensation involves taking compensation to extremes.

Alfred Adler was born in Rudolfsheim, near Vienna, Austria. His father was a grain merchant, and his mother was a stay at home mom. Alfred was born into a religiously nonobservant family, but they were ethnically Jewish, and they were lower middle class. Adler was profoundly affected by the death of a close younger brother, his own near death experience, and from the rickets he suffered from as a child. 2010) He was constantly trying to outdo his older brother even though he was physically impaired.

He was a mediocre student who had dedicated his life to becoming a doctor because of his own and his brother’s illnesses. The adversity he faced as a child will go on to be the basis for his personality theory (Edwards.

This paper is to outline and describe the psychologist Alfred Adler and his theory of personalities. It will draw connections with his personal life, and also present research that not only supports his theories, but also opposes the theories (Edwards 2010). Adler, although being a mediocre student, he achieved a medical degree from the University of Vienna. After getting his medical degree, he set up a private practice in the Leopoldstadt district of Vienna (Edwards.

While there, he gained a reputation for being a hard worker and being very good at diagnosing. In November 1898, Sigmund Freud invited him to meet in a weekly group that discussed psychology; this would be the beginning of a relationship that would turn into a heatedRelated Documents.

Psychoanalytic Personality AssessmentIn an attempt to understand the human psyche as it relates to personality, theorists such as Sigmund Freud, Carl G. Jung, and Alfred Adler all developed their theories to describe personality. To better understand the mentioned theorist’s beliefs it is necessary to compare and contrast the various psychoanalytic theories characteristics as well as to make mention of the portions that are agreeable or disagreeable. Also, the stages of Sigmund Freud's theory and Freudian. Psychodynamic TheoristThe foundation of psychodynamic theory consists of four main elements. These elements include three levels of awareness, three psychic structures of personality, the psychosexual stages, and the defense mechanism used to cope with anxiety (Cervone, & Pervin, 2010).

Within this paper will be an explanation of psychodynamic theory as Sigmund Freud designed it and how neo-Freudian theorist such as Alfred Adler, Carl Jung, and Erik Erikson advanced Freud’s concepts. Bernie Sanders personality is very complex. The most important personality characteristics reflected on his behavior and life outcomes are the following; he is an analytic, compassionate, sincere, altruistic, passionate, moral, profound, persistent, wise, hardworking, humble, liberal, private, leader, outspoken, humorous, and caring individual. According to Psychologist Alfred Alder, there is a basic motivation within ourselves to strive for perfection. “Perfection” is not being a perfect individual. Alfred Adler was born outside of Vienna, Austria on February 7, 1870.

He was the third child (second son) of what would eventually be seven total children. As a child, Alfred developed rickets, which kept him from walking until he was four years old. At five, he nearly died of pneumonia.

At one point, Adler heard the doctor tell his father that “Alfred is lost”. It was around this time that Adler decided to become a physician. (Corey 2005)Due to frequent illness, Adler was pampered by his mother.